|

|

|

Current News |

|

Chemistry A to Z |

|

About Internetchemistry |

Crystal-to-Metal - Transformation on the Nanoscale |

|

Unique "near-field" microscopy at the MPI f�r Biochemie (Martinsried near M�nchen) allowed, for the first time, viewing on the nanoscale the spontaneous appearance and growth of metallic puddles that mark the transition from an electrically insulating material itno an electrically conducting one. The research may lead to a better understanding of superconductors-materials that conduct electricity without energy loss - or development of better materials for powering high-speed electronics. In a paper published on Friday, 14 December 2007, in Science, Markus Brehm und Fritz Keilmann join an international team in describing a novel approach to viewing Mott's transition in vanadium dioxide. Their co-authors are Mumtaz Qazilbash, Greg Andreev, Brian Maple and Dimitri Basov of the University of California-San Diego; Alexander V. Balatsky of the Theoretical Division and Center For Integrated Nanotechnologies in Los Alamos; and Byung-Gyu Chae, Hyun-Tak Kim and Sun Jin Yun of the IT Convergence and Components Lab, Electronics and Telecommunication Research Institute in Korea. |

|

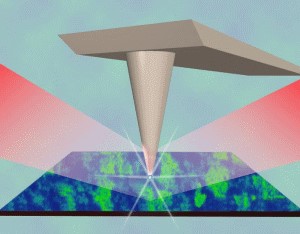

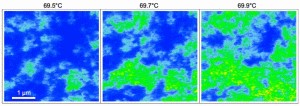

Materials such as copper metal contain electrons that are mobile enough to conduct an electrical current. In conducting materials such as copper, gold, silver, or aluminum, electrons do not hinder one another and are free to move about the lattice structure of the material. In more-complex crystal oxides, such as vanadium dioxide, electrons can become influenced by nearby positively or negatively charged particles, and their movement can become hindered. These materials are known by physicists as "correlated materials." Correlated materials include superconductors or semiconductors-crystals peppered or "doped" with atoms that may donate mobile electrons to the solid. Correlated materials can exhibit extraordinary changes in their physical properties, such as transforming from an insulating material to a conducting material, when subjected to relatively small changes in pressure or temperature. Vanadium dioxide begins becoming conductive when reaching 68�C, and is fully metallic already at 71�C. On cooling the conductivity disappears. For decades scientists have puzzled over how this transformation to a fully metallic state - known as "Mott" metal-insulator transition - occurs. Condensed-matter spectroscopist D.N. Basov and theorist A.V. Balatsky argued that the transition begins when tiny metallic puddles begin forming at sites of impurities or imperfections within the lattice, and looked out how to make such puddles visible by some sort of "nanoscale viewer". The infrared nanoscope developed in the lab of F. Keilmann offered a fitting solution. This instrument had already yielded widely recognized results. Recently it enabled infrared spectral inspection of single viruses of below 20 nm thickness (a human hair is 80 000 nm thick) or of modern transistors of 65 nm size. D.N. Basov set out to visit Martinsried for a successful study of Korean-prepared and characterized VO2 crystals. M. Brehm, then postdoc, observed the initially structureless, flat crystal becoming, in the critical temperature region, full of tiny metal inclusions that grew and finally coalesced. These infrared nanoscope images have revealed for the first time a new type of metal "phase" characterized by unusually strong electron correlation existing only during the transition of the material from its insulating state to its conducting state. The infrared nanoscope works at long wavelength of 10 000 nm. It is capable of resolving these tiny objects only because its light is virtually fine-focused by the AFM's probing tip. This mechanism is akin to how an automobile antenna concentrates radio waves into the receiver. The metal puddles highly reflect the infrared nano-focus and thus become highlighted in the image. The new findings will help researchers worldwide better describe and understand underlying physical laws of how charges propagate through correlated materials. The research could help materials scientist understand how to precisely dope a material with specific atoms in order to optimize conducting or superconducting behaviour or, conversely, to create materials impervious to electrical conductivity or magnetic influences. "What is extremely exciting about this research is that four different laboratories with complementary disciplines cooperated to use this infrared nanoscope in its first successful application for solving a solid-state physics puzzle," Keilmann said. |

|

|

|