|

Related Topics: |

|

|

|

Current News |

|

Chemistry A to Z |

|

About Internetchemistry |

Synthetic Magnetic Fields for Ultracold Neutral Atoms |

|

For the first time, physicists have used laser light to create "synthetic magnetism," an exotic condition in which neutral atoms suddenly begin to behave as if they were charged particles interacting with a magnetic field - even though no such field is present and the atoms have no charge. The achievement provides unprecedented insights into fundamental physics and the behavior of quantum objects, and opens up entirely new ways to study the nature of condensed-matter systems that were barely imaginable before. There are many phenomena of urgent interest to physicists, such as the action of electrons restrained in two dimensions in a magnetic field, that are difficult to investigate in conventional materials such as semiconductors. Not only is it hard to control the numerous variables involved, but there are always defects and irregularities in the experimental samples. Nonetheless, such research is important both to basic quantum mechanics and to applied fields such as quantum computing and information science. Synthetic magnetism provides a way to model and examine such quantum systems while exercising precision control over the parameters. |

|

|

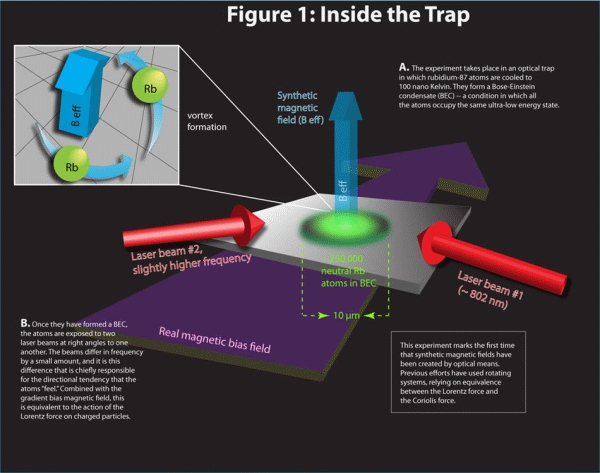

"The creation of synthetic magnetic fields for ultracold neutral atoms enables previously impossible experiments in these most quintessential of quantum mechanical systems," says research group leader Ian Spielman, a Fellow of the Joint Quantum Institute and physicist at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Spielman and colleagues describe the work in a paper published in the Dec. 3, 2009 issue of Nature. The team began by taking a population of rubidium-87 atoms, decelerating them with a Zeeman slower and then confining them in a magneto-optical trap. The atoms then underwent evaporative cooling in a magnetic trap and then an optical-dipole trap until approximately 250,000 remained at a temperature of about 100 nano Kelvin. Under those ultracold, low-energy conditions, the atoms formed a Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC) – a strange state of matter in which most of the atoms in a group occupy the same minimum-energy quantum state, somewhat as if they collectively constituted a single "super atom." A small, spatially varying, magnetic bias field was applied across the BEC, producing a gradient that affected the atoms differently depending on their position along one axis of the trap. [See Figure 1.] Then two near-infrared (wavelength, λ=801.7 nm) laser beams, oriented at 90 degree angles to each other, were aimed into the atoms. The scientists adjusted the beams to have very slightly different frequencies. The cumulative effect of the gradient field and the two laser beams altered the properties of the atoms (in particular, their momentum along one axis) in a way that depended on their location in the trap and their interaction with the beams.

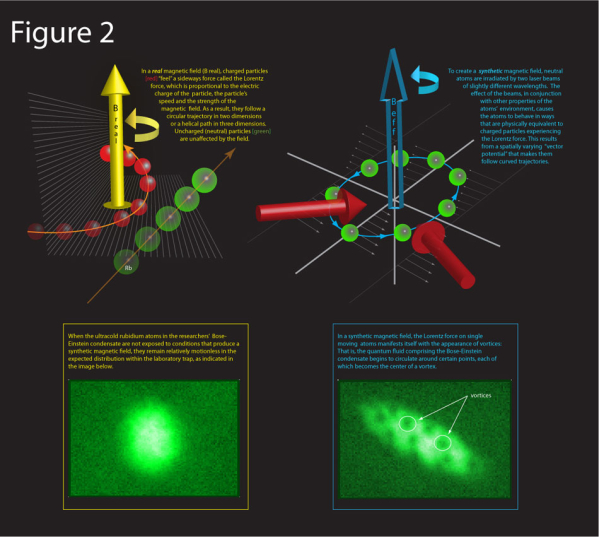

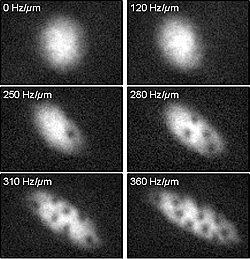

Those differences, the researchers found, could be tuned by making slight changes in the frequencies of the laser beams, in effect conferring a "charge" on sub-populations of the neutral atoms and creating a synthetic magnetic field to which they reacted. By varying the beams and the gradient, and thus controlling the position-dependent momentum potentials of the atoms, the team observed that – as predicted in a theory paper Spielman had authored earlier this year – atoms at specific points in the trap began to move in a way mathematically equivalent to the way a charged particle would revolve in a magnetic field. The effect caused small quantized vortices of atoms to enter the BEC. [See Figure 2.] To confirm and measure the magnitude of the phenomenon, the team took pictures of the BEC approximately 25 milliseconds after shutting off all fields and beams in the trap. Images of the expanding atomic cloud clearly showed that when the synthetic magnetism was not present, the atoms in the BEC had the customary distribution. But when the synthetic field was activated, vortices were plainly visible – a clear indication that an optically induced synthetic magnetic field had been created for the first time.

The results are expected to have a substantial impact on various fields of inquiry in quantum science, especially the behavior of electrons confined in different geometries, as they are in real materials. In particular, it will allow researchers to explore how the energy spectrum of electrons in a crystal lattice varies with the magnetic field applied to the system. (This subject produced the now-famous theoretical plot of energy levels called "Hofstadter's butterfly" because of its elegant, wing-like curves.) In addition, synthetic magnetism should prove valuable in characterizing aspects of the quantum Hall effect, a phenomenon observed in two-dimensional systems of electrons in a magnetic field. In that situation, the electrons naturally tend to follow circular ("cyclotron") orbits; and the energy levels of those orbits are quantized. The National Institute of Standards and Technology uses the quantum Hall effect to define the international standard of resistance. Further improvements on the synthetic magnetism work, Spielman says, should allow new ways to investigate these and other phenomena. "By adding an optical lattice potential to our synthetic magnetic field," he says, "we have the opportunity to create both long anticipated systems such as the Hofstadter butterfly - an iconic pattern of energy levels for non-interacting particles - and potentially to realize totally new states of matter such as quantum Hall states of bosons." The research was partially supported by the Office of Naval Research, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the Army Research Office and the National Science Foundation through the NSF Physics Frontier Center at the Joint Quantum Institute. The Joint Quantum Institute (JQI) is a research partnership between University of Maryland (UMD) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology, with the support and participation of the Laboratory for Physical Sciences.

NIST press release: JQI researchers create 'synthetic magnetic fields' for neutral atomsAchieving an important new capability in ultracold atomic gases, researchers at the Joint Quantum Institute, a collaboration of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the University of Maryland, have created "synthetic" magnetic fields for ultracold gas atoms, in effect "tricking" neutral atoms into acting as if they are electrically charged particles subjected to a real magnetic field. The demonstration, described in the latest issue of the journal Nature, not only paves the way for exploring the complex natural phenomena involving charged particles in magnetic fields, but may also contribute to an exotic new form of quantum computing.

As researchers have become increasingly proficient at creating and manipulating gaseous collections of atoms near absolute zero, these ultracold gases have become ideal laboratories for studying the complex behavior of material systems. Unlike usual crystalline materials, they are free of obfuscating properties, such as impurity atoms, that exist in normal solids and liquids. However, studying the effects of magnetic fields is problematic because the gases are made of neutral atoms and so do not respond to magnetic fields in the same way as charged particles do. So how would you simulate, for example, such important exotic phenomena as the quantum Hall effect, in which electrons can "divide" into quasiparticles carrying only a fraction of the electron's electric charge? The answer Ian Spielman and his colleagues came up with is a clever physical trick to make the neutral atoms behave in a way that is mathematically identical to how charged particles move in a magnetic field. A pair of laser beams illuminates an ultracold gas of rubidium atoms already in a collective state known as a Bose-Einstein condensate. The laser light ties the atoms' internal energy to their external (kinetic) energy, modifying the relationship between their energy and momentum. Simultaneously, the researchers expose the atoms to a real magnetic field that varies along a single direction, so that the alteration also varies along that direction. In a strange inversion, the laser-illuminated neutral atoms react to the varying magnetic field in a way that is mathematically equivalent to the way a charged particle responds to a uniform magnetic field. The neutral atoms experience a force in a direction perpendicular to both their direction of motion and the direction of the magnetic field gradient in the trap. By fooling the atoms in this fashion, the researchers created vortices in which the atoms swirl in whirlpool-like motions in the gas clouds. The vortices are the "smoking gun," Spielman says, for the presence of synthetic magnetic fields. Previously, other researchers had physically spun gases of ultracold atoms to simulate the effects of magnetic fields, but rotating gases are unstable and tend to lose atoms at the highest rotation rates. In their next step, the JQI researchers plan to partition a nearly spherical system of 20,000 rubidium atoms into a stack of about 100 two-dimensional "pancakes" and increase their currently observed 12 vortices to about 200 per-pancake. At a one-vortex-per-atom ratio, they could observe the quantum Hall effect and control it in unprecedented ways. In turn, they hope to coax atoms to behave like a class of quasiparticles known as "non-abelian anyons," a required component of "topological quantum computing," in which anyons dancing in the gas would perform logical operations based on the laws of quantum mechanics. |

|

|

|