|

Related Topics: |

|

|

|

Current News |

|

Chemistry A to Z |

|

About Internetchemistry |

Synthetic chemical offers solution for crops facing drought |

|

RIVERSIDE, Calif. – Crops and other plants are constantly confronted with adverse environmental conditions, lowering yield and costing farmers billions of dollars annually. Plants use specialized signals, called stress hormones, to sense difficult times and adapt to stressful conditions to enhance survival. Of the various stress hormones, abscisic acid (ABA), produced naturally by plants, has emerged over the last 30 years as the key hormone that helps plants cope with drought conditions. Under such stress, plants increase their ABA levels, which helps them survive the drought through a process not fully understood. So critical is this endogenous chemical to plant survival that researchers have engineered new drought-resistant crops by tinkering with the ABA pathway. |

|

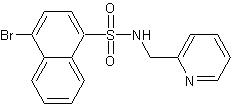

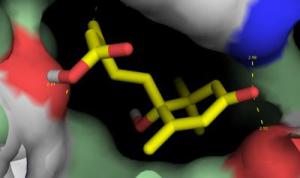

For years, scientists have contemplated spraying ABA directly onto crops to enhance their protection in times of stress. But ABA is a costly, complicated and light-sensitive molecule that has not found use in agriculture. Now new research from the laboratory of Sean Cutler, an assistant professor of plant cell biology in the Department of Botany and Plant Sciences at the University of California, Riverside, suggests the possibility of spraying stable synthetic chemicals on plants to enhance stress tolerance during times of drought and improve yield. Using a method called chemical genomics, pioneered by UC Riverside researchers for studying plant biology, Cutler identified pyrabactin, a new synthetic chemical that turns on the ABA signaling pathway in Arabidopsis, a small flowering plant used widely in plant biology laboratories as a model organism. His lab then used pyrabactin to fish out a receptor for ABA – a highly controversial topic involving retractions of scientific papers as well as the publication of papers of questionable significance. A receptor is a protein molecule in a cell to which mobile signaling molecules may attach. Usually at the top of a signaling pathway, it functions like a boss relaying orders to the team below that then executes particular decisions in the cell. "Scientists have been trying to solve the ABA receptor problem for more than 20 years, and claims for ABA receptors are not easily received by the scientific community," said Cutler, who came to UCR in 2007 from the University of Toronto. "We screened thousands of chemicals for one that mimics ABA. We found pyrabactin activates some of the ABA receptors in plants and is an excellent mimic of ABA. Moreover, unlike ABA, it is stable and easy to make. It therefore suggests a highly effective chemical strategy for improving plants' ability to survive under low-water conditions, potentially benefiting farmers in drought-prone areas worldwide." Cutler's approach highlights the power of the chemical genetic approach for uncovering new leads for agrichemistry and, in turn, using those leads to understand a biological process. "This is a striking example of how a chemical allowed us to solve a problem that genetics has been struggling with," he said. "Clearly, chemical genetics can be used to bypass some of the limitations that slow down classical genetic analysis. Not too long ago, the United Nations called for a 'blue revolution' - the water equivalent of the green revolution - of improved water management and sharing. We have proven that we can enlist chemicals that modulate stress responses in crops as soldiers in the blue revolution. Now our goal is to design the best chemical soldiers possible." Because of the prior questionable data in the ABA field, Cutler, the research paper's lead author, took the unusual step of sharing his data with key competitors and turning them into collaborators before publishing the results. Several labs working in the ABA signaling field tested the ABA receptor that Cutler's group identified, and validated his results. Scientists from these labs are co-authors of the research paper. "Several high-profile papers have tried to claim discovery of ABA receptors but their research could not stand the test of time, and these papers were ultimately withdrawn," said Natasha Raikhel, the director of UCR's Center for Plant Cell Biology, of which Cutler is a member. "I believe this time, Dr. Cutler and his team have isolated a true ABA receptor." Next in the research, Cutler and collaborator Brian Volkman of the Medical College of Wisconsin will work on deducing the structure of receptor-bound ABA and use this information to guide the design of new chemicals that turn on the ABA signaling pathway. Cutler and collaborators also plan to further understand how the ABA receptors affect plant physiology. Cutler was joined in the research by colleagues at UCR; the University of Toronto, Canada; UC San Diego; Universidad Politecnica, Spain; University of Ontario Institute of Technology, Canada; UC Santa Barbara; and the Medical College of Wisconsin. The University of California, Riverside is a doctoral research university, a living laboratory for groundbreaking exploration of issues critical to Inland Southern California, the state and communities around the world. Reflecting California's diverse culture, UCR's enrollment of about 17,000 is expected to grow to 21,000 students by 2020. The campus is planning a medical school and has reached the heart of the Coachella Valley by way of the UCR Palm Desert Graduate Center. The campus has an annual statewide economic impact of more than $1 billion. To learn more, visit www.ucr.edu or call (951) UCR-NEWS. |

|

|

|